Article 2011 / 2009 / 2008 / 2007 / 2006

New Classic of Mountain and Seas

Qiu Anxiong

Translate By Philip Tinari

New and old are relative concepts. New, novel, nouveau, innovation, these words, full of life and possibility, delight us with their freshness and vigor. Old, antiquated, senescent, pass, these words are the frozen epitaph of time's passage, balefully indicating the steady erosion caused by months and years. No wonder people embrace the new and scorn the old. So has it been since the beginning.

There is a splendid bit of teaching in the Book of Great Learnings(basic learning of acient China): If you renew yourself, then you must renew yourself again, each day, without end.In this we clearly find the central philosophical concepts of the Book of Great Learnings: The way of morality, new humanity and the ultimate goal of goodness. The Book of Great Learnings aims to illuminate and edify people in the proper way of study and self-cultivation to achieve goodness and morality. It is a road map to new life, and not just for one day, but until the very end. It seems the ancients were not as obstinate in upholding tradition as we modern people like to imagine. They, too, sought out new life, perhaps just in a different way.

Time continually renews itself, the past never repeats itself, and each split second is new. This is all common knowledge. But every split second becomes a past moment the instant it expires. The new and the old extend each other, enhance each other and, in the end, constitute each other. The objects of the world are produced and extinguished in the continual flux of time. New things gestate in the belly of the old.

These days, most people consider new and old to be mutually exclusive concepts. The new is completely novel; the old, totally outdated. The old can be eradicated for the sake of the new and creation of the new world necessarily implies destruction of the old world. But somehow the world that emerges from the gap between us and the old order never seems to add up to our idealization of it. It's never as perfect, nor nearly as peaceful. Contrarily, the contradictions and chaos seem only to increase. No one has really thought deeply enough about the intimate relationship between the new and the old. Most people in China automatically equate new with all things Western. Conversely, all things old are, then, constituted as being Chinese. This thought-pathology has persisted for a long time and is almost an article of faith now. Without fanfare, it has imperceptibly formed a powerful archetype in our everyday thinking: Western stuff is cutting edge, Chinese stuff is backward. In the wake of the ever-advancing West, we consciously debase ourselves. West-worship intertwines with a kind of blind resentment to form a mentality whereby we continually overcompensate for perceived lack. We fail to achieve the golden mean, every step is somehow a misstep and we constantly imagine ourselves to exist in someone else's shadow. Our present is the West's past. We lag decades behind. This ideology is China's tragic present.

The relationship between the old and new is no where near as simple. It more resembles a tree, an organic entity. In the beginning it is just a tiny sprout. But the new sprout comes from the old seed. Old and new are mutually dependent. When the tree grows up, big and tall, it needs numerous branches, countless leaves and a solid trunk to live. The roots and trunk are old, the branches and leaves continually renewed. Lacking even one of these, the tree can't live. No matter how long the tree lives, even for a thousand years, the basic formula holds true. Furthermore, today's trunk is yesterday's branch and today's branch is tomorrow's trunk. The ecology of new and old in human culture is no different. The problems and questions in contemporary Chinese society all stem from the fact that this basic question has never been satisfactorily resolved.

While China actively sought modernization, it simultaneously became critical of tradition, going so far as to completely repudiate it. China's modernization was based on a superficial misread of Western culture. In its overzealous and unlimited appropriation of all things Western, it buried this fundamental fallacy for future generations. Modern China now faces all manner of crises bereft of traditional roots, especially cultural, spiritual and religious. These are the lifeblood of the people and the nation, which, like the roots and trunk of the tree, provide nourishment and support. Even the anti-traditionalism of the May Fourth movement was still grounded in traditional culture. Spiritually, it was still in the same vein as what had come before. The May Fourth refusal was well-intentioned and was issued from a solid foundation. It was a call for the renewal of self.

The biggest mistake of the post-Liberation modernization plan was to jettison traditional Chinese concepts of development, opting instead to import wholesale a European model stressing an idealist political system backed up by trenchant belief in mass culture, science and technology. Culture and society became simple tools for political propaganda. This repudiation of tradition reached its apogee in the Cultural Revolution. Jettisoning traditional characters in favor of the current system of simplified characters is profoundly indicative of this assault on tradition.

Post-Cultural Revolution policy of opening and reform has only hastened the pace of cultural transformation, as economic considerations replace political standpoint as the arbiter of life and death. Chinese born after Liberation display little sensitivity to traditional culture, their cultural memories already usurped by the Westernized (or, more accurately: colonialized) trappings of contemporary society. Today, traditional culture has been isolated into an extremely marginal position. It's become a way to kill time after retirement, or a way to package products designed for western markets. Traditional culture is now little more than fabricated folk customs displayed in museums to gawking crowds while mainstream culture continues inexorably on the path toward colonialized commodification. The fissure between traditional culture and contemporary social life has resulted in the ossification of the once-vibrant interplay of old and new.

The age old sense of morality is rarely encountered anymore. This general spiritual impoverishment is reflected everywhere. Scholars, farmers, business people, workers and students alike have all turned their backs on society, replacing the old sense of social responsibility with the single-minded pursuit of immediate gain. Moreover, this gain is only calculated with respect to themselves, irrespective of its impact on other people, society or the nation as a whole. Examples are legion. Officials bend the rules for personal gain or engage in outright fraud. Workers make harmful products. Farmers produce unhealthy crops. Merchants have no credibility, no good intentions and no sense of shame. Teachers have no ability, no morality, no kindness and no ardency. Students have no patience, no language, no interest and no passion. Worst of all, there are few who do not fall within these broad characterizations. People are impetuous. They grasp after the smallest gain which appears before their eyes, completely oblivious to long-term benefit. All this is the result of a root which has been severely damaged and when the root and trunk are sick, can the branches and leaves possibly be well? The implicit value of new and old is not simple nor can it be arbitrarily determined by blind judgments of right and wrong. Those seeking genuine moral and spiritual renovation should seek the way with a wide historical compass. Only then can they avoid the confused wanderings of the recent past.

Mountain

When the universe was formed there appeared the heavens and the earth. Beneath the heavens there were great oceans, masses of land, tall mountains and flowing rivers. Here life took root. We humans depend upon the earth's existence and continued vitality.

The mountain is the highest point on the surface of the earth. There is a bit of Buddhist thought which runs: the common world is full of imperfection, peoples hearts are full of unclean thoughts, so too is the surface of the earth uneven, full of mountains, peaks, valleys and cliffs. Scientifically, these are but geologic phenomena, created by the action of tectonic plates, the lifeless things which make up the crust of the earth.

The ancients were animistic, believing all things to be invested with spirit. To them, the mountain was a deity, and so they worshipped it and prayed to it. Even the emperor would bow to the mountain and make sacrifices to propitiate the gods. The ritual respect which the ancients showed for the mountain was not only tacit acknowledgement of transience and change, but also of awe of natures unpredictability. It was their way of re-paying natures bounty. There is a quote from the Classic of Yu Gong: Silk, bamboo, feathers, hides, gold, stone, salt, and iron, all things of use to man come from known mountains. Clothes, food, tools, domiciles, all things made by man are made with materials bequeathed by the mountain, the river and the land. The ancients obviously recognized their great debt to nature. They cherished the natural environment and would not knowingly harm it. The ancients had a saying: When hunting, do not destroy the forest. When fishing, do not drain the river. There was another common saying: Do not kill birds in spring, because back in the nest there is a hatchling waiting mothers return. Here we find hints of the urge to restrain man and conquer nature, but it was more their way of respecting natural law and achieving harmonious balance with other forms of life. The ancients recognized that the fate of man and the fate of nature were inextricable. This is quite different from the Western ideal of shaping nature to fit human needs. Traditional Chinese culture believed that all life existed in concert with nature. The ancients saw humans, though chief among all animals but essentially the same as other forms of life, comprising but a part of the overall ecology. Thus, humans emulated nature, lauded nature and believed that only within nature could truth be achieved.

The essential trend of modern Western thought has been entirely different. One by one, the traditional religious taboos have been broken. Taking proof as the basis of truth, the West made science the order of the day. Darwin's theory of evolution not only stole gods thunder as creator of man, it also instigated a new order of materialist belief: Life was only out to perpetuate itself. This narrative of the natural world gradually became a gospel principal of life and eventually the governing philosophy of human existence. As god was dethroned in favor of chemistry, life and death became a commercial transaction between the organic and inorganic while spirit was remaindered as by-product of organic activity. Under this scheme, man had truly and finally left the Garden of Eden. Naked and alone, perpetually at odds with a cold and faceless nature, he was left to struggle for survival. Might had made right. The strong not only survived, they did so with the blessing of morality.

Man��s material desire knows no limits. The mountains, rivers and even the earth itself have become little more than warehouses for mans greed. It's not just destroying the forests during the hunt and drying up the river to get fish anymore, now it's obliterating entire species for wood, leveling mountains for minerals and tunneling the earth for oil. We plot against each other for control of natural resources. We fight each other for the very right to survive.

It's undeniable: Nature is pulp beneath our feet and man has truly become master of himself. With nature dead, what will future generations measure themselves against? Only time will tell.

Seas

In traditional Chinese culture, the sea was conceived as the end of the world. No one was clear what exactly was on the other side. In the Classic of Mountain and Seas we find accounts of mythical beasts and birds, strange insects and weird fish, as well as a country of creatures, four-limbed like us but possessing supernatural characteristics, living across the ocean. For a thousand years, this book represented the extent of knowledge of the outside world, giving our tillers of fields and weavers of cloth cause for wild imaginings. Except for minor contacts with pirates and emissaries from Japan, the Chinese were unable to grasp the idea that actual nations of people existed elsewhere. The great and beautiful land around them was all they knew. Heroes of the past sought glory and fame here. Likewise foreign encroachment was always because outsiders coveted the fecund fields, beautiful mountains and abundant rivers of the homeland. Conversely, lands across the seas were the home of supernatural beings and the destination of strange hermits. Admiral Zheng He's grand journey over the seas during the Ming dynasty was but a brief moment of glory. The ocean soon became Europe; the path between, a conduit of wealth; the confrontation of cultures, the beginning of colonial history. Not surprising then that the Chinese still extol ancient glories.

In fact the situation shifted quite early on. The ocean has been China's nightmare for the last 100 years. Opium, weapons, capitalism, churches, science and technology, ideology, political idealismall these things rode the waves across the ocean and disembarked on these shores. Facing the aggression of colonialism, the Chinese appeared weak. The tillers of fields, who had been born to propitiate nature and compromise for the general good, were helpless against the will to wrench open the borders. China gradually lost its original political philosophy of leading by moral example in its effort to cope with the power of will. The confrontation instigated an unprecedented crisis of confidence in the Chinese people as self-doubt rippled through the culture. Countless people departed this once-mythic golden land to embark on their own journeys abroad, leaving behind scenes of ruin. The ocean once again became the source of new life and possibility.

Conquest of the sea re-constituted the instrinsic self-sufficiency of the homeland and the familiar sounds of the farm were drowned out by the clatter and clang of iron and steel. We became estranged from ourselves, fatally separated from our originally pastoral nature. We have lost our intimate appreciation of antiquity. We have forgotten how to lose ourselves in contemplation of the world. We have lost our traditional politesse and dignity. We have lost the ability to think deeply and reflect profoundly. We have lost our sense of history and learning. We have lost our lofty aspiration. We have lost our sense of gratitude toward nature. The great spiritual chain of being has been sundered and we are adrift.

The homeland no longer protects us and so we detest it. We try to erase it from our memory. We want the blue of the ocean to engulf the golden hue of the homeland. Let us float! Float toward the utopia of imagination.

Classics

The classic is a standard with universal applicability. Those books from antiquity which we term classics are paradigms which hold for a hundred generations. From antiquity to the present day, the classics guide us, bearing immutable truth transcending the limitations of time. The Yi Jing, Nei Jing and the Classic of Mountains and Seas are living cultural relics passed down since earliest antiquity. They are the well-spring of Chinese civilization.

The Six Classics, compiled by Confucius during the Zhou dynasty, remain the basis of Confucian learning. The Classic of Dao and the Classic of Nanhua, edited by Laozi and Zhuangzi, illuminate the mysteries of yin and yang. The philosophy of Sakyamuni, the Buddha, illuminated causality in worldly affairs. His wisdom took root in China where it was broadened and elaborated. These great schools of thought comprise the three pillars of the Chinese cultural tradition. Having persisted for thousands of years with continual renewal, they truly deserve the name classics.

The Yi Jing is a kind of astrological compendium, using symbols of divination to probe the interplay of time and space and elaborate scientific principles. It is the founding text of the thought of the Spring and Autumn period. The Nei Jing is the classic of Chinese medicine. Collecting the teachings of two Chinese physicians, it lays out a schematic for preserving health and treating illness. In essence it advocates natural methods of balancing yin and yang. These texts too have earned the epithet classic.

The Classic of Mountain and Seas, on the other hand, is a somewhat different case. It is alone in recording the cornucopia of creatures and beasts and spirits and deities, as well as all sorts of unimaginable things, both in the homeland and abroad. Seventy-five percent of the text is stories of monsters, deities and spirits. Even though the stories have been passed down through the ages, the Classic of Mountain and Seas has been largely ignored by history. Some suggest that, originally, the Classic of Mountain and Seas had no text at all and was only a series of pictures and the subsequent words were only appended later. The majority of the images were re-printed over and over again over a long period of time and nowadays we can only make out a few dating back to Sima Xiang ru's Zi Xu Ci from the Han dynasty. The text of the Classic of Mountain and Seas was of limited value in terms of political management or pursuit of enlightenment. Its main purpose was simply to increase knowledge, useful or otherwise, and so it cannot really be called a classic. The Classic of Mountain and Seas never enjoyed the kind of scholarly attention enjoyed by the Yi Jing or the writings of Confucius. A few Daoist scholars bothered to annotate it, but it never achieved the status of scholarly material. It's nearly inconceivable that, historically, the volume should still be referred to as a classic. But on another level, it makes sense. Even though sages never bothered themselves with the supernatural bestiary, for common people, the stranger the story, the more it aroused their interest. Thus, its great longevity. It was, quite simply, a phenomenon of popularity.

I, like the rest of the common people, also like the Classic of Mountain and Seas. It's not only a good read, it's a spur to the imagination. When a strange thought pops into my mind, I grasp hold of it and continue writing. Are the stories in the Classic of Mountain and Seas true? Even the wisest among us, don't know for sure. What about our lives? What about the world-at-large? The Buddha says, The world of appearances is false.He goes on: everything has its proper order. We should look at the world as if having just woken from a dream, as if seeing the first dew of the early morn. It's the moment of contact.

I have already forgotten my original motivation for writing the New Classic of Mountain and Seas. I suppose I have seen many strange things go on in our society. So many feelings, so many sensationsI can't not speak of them. So I chose a particularly unedified point of view as my lens on contemporary society. The menagerie of beasts becomes metaphors for these phenomena. It's my way of poking a bit of fun. People today use all manner of sophistry to investigate the world. From what's around them they extrapolate to the furthest reaches of the universe. Whatever can be thought, heard or seen has already gone as far as it can go. Knowledge is too broad, individual life is too short, tangible things are far too few. The world in front of our eyes has fragmented into intellectualized symbols, vast, broad, endless. An individual facing this kind of world can only feel an overwhelming kind of nothingness. Spiritually, there is little that can be termed unified. Thus we fall prey to a profound sense of terror punctuated by argument and struggle. This is the promise of civilization? You will have to arrive at your own answer.

I really don't have the temerity to write a new Classic of Mountain and Seas. I just jot down thoughts for my own entertainment which I hope people will read in their own way. If we can share a grin between us, all the better. Besides entertaining myself, if I can entertain others, I reap an unexpected reward. Whatever the case, I wrote this piece in the grip of the moment; the name of the piece likewise came to me rather spontaneously. Nothing more than that. This piece is a fragment of a moment plucked from a transient life. Read into it at your own risk.

And that's the way it is.

Qiu Anxiong

April, 2005. Chengdu, Yiguan Temple

The World Seen from afar

Chang Tsong-zung

In an early essay about the responsibility of an artist Qiu Anxiong lamented the cultural decadence of China's present predicament, and criticised the contemporary art scene for not leading a noble example.(Reflections on the Present Predicament and Responsibility of an Artist, summer 2000). He suggested that the artist should lead the way in being true to his chosen path, and bear his responsibility as keeper of cultural heritage and spiritual vigilance; he should resist the hollowness of existence by his integrity and commitment to truth in life. It was a critical essay on modern Chinese culture that did not go with the style of the art Qiu was making at the time. A devout Buddhist, and self taught student of Confucian classics, Qiu's painting is the paradigm of quietude and detachment, depicting colour planes that suggest sky and sea meeting at a horizon. He painted in oil when taking an advanced degree at Kassel, Germany, and then turned to landscape inspired by old Chinese masters - visions equally calm and timeless - working in both oil and ink. In 2004 Qiu moved to Shanghai from his hometown in west China and became interested in video; Jiangnan Poem, his first video, was made in 2005, followed by In the Sky at the end of the year.

The continuity of Jiangnan Poem with Qiu's earlier work is evident. There is the same poetic sensitivity that seeks out the quickness of life, the same tranquillity and unspoken passion stirred by the passage, and return, of time and season. The title is taken from the poetic name of a metric pattern in classical verse. A simple work, austere and undemanding, it compels attention by its unpretentiousness. Its beauty depends on the universal sentiment stirred by the return of spring, when we are all lifted with hope brought by the stirring of life and community. As a step forward from his paintings this video represents a close up view of the natural world which hitherto was only seen from afar.

The drama of the world began to unfold with Qiu's first animation In the Sky. This is a charming narrative made with the technique of ink painting, which the artist did on a single canvas so that each successive image can be altered in stages over the previous one. It is the drama of urbanisation seen from the point of view of the countryside, and each stage of development is accompanied by forms of life that respond to human encroachment with evolutionary ingenuity, culminating with a large rat mounted on a growing hill of soil in the final scene. The story does not denounce development outright, giving instead a lyrical vision of the outcome of exploitative growth. The medium of ink, melting and smouldering into changing chimera of the same landscape, brings across a strong message of the impermanence of the material world and the inevitability of change. Like any good Confucian, Qiu has an eye on the cycle of life, and this work is mindful of the power of regeneration, even when the outcome may not be entirely to the benefit of humans.

Shan Hai Jin(Classic of Mountains and Seas) is an old book of geography edited into the present form sometime before the 2nd century AD. The book describes the wide world beyond the Middle Realm, complete with a catalogue of desirable natural products, strange creatures and variant forms of humanity. It provides a vision of the known world at the time, and titillates mans imagination about the magic of the unknown beyond. Its na?ve description of creatures blessed with special powers is the model for Qiu in this story of contemporary world and its politics. The New Book of Mountains and Seas is allegorical in its reference to historical events, the narrative takes military incursion of western powers into pre-modern China as the entry point into a world invaded by strange beasts with alien powers. The story gradually leads into recent post-9-11 events thinly masked as a fantastic tale. Looking at a distance into today's world relieves the viewer from claustrophobic identification, and sets him adrift in the strange universe of contemporary life. This is what one sees by adopting by pre-modern eye, and the artist seems to suggest that few essential advantages have been gained by populating the world with all the monsters we have created.

Yan Nan (Flying South), is an animation newly completed at the end of 2006. While evoking with its lyrical title the natural order of the seasons, this is yet another tale about the story of modernisation. The regulated fields, the general conflagration, the library with its repetitive tome, caged bird, mutating animals and mass burial all point to the parallel story of animal transmitted plagues and ideological politics. Both stories are current memories in the Chinese mind. But it is also the story of the recent century for all of us. Modern man has developed the power to both generate and control plagues; when seen in perspective, we find that human population has been manipulated in strikingly similar manner by messianic politics in the recent century.

In the medium of film, where both time and space are extended beyond the common? experience, it is the power of looking into the distance that stirs the imagination. The perspective Qiu brings to the viewer cuts across historical time, and lifts him to a distant vantage point. From this point the artist sees the ills of our times with greater clarity, and may better identify his artistic responsibilities. Remembering the vast expanse of sky and sea in the artist's paintings, it becomes evident that Qiu has been training his vision for some time; he has arrived at this perspective by stretching his vision into the horizon, where all the world's dramas are but distant tremors, and all human strife are inconsequential disputes within the greater order of the universe.

Qiu Anxiong's Theory of the Evolution of Mythology

By Yale Yin

Western myths are always related to reality; Chinese myths, on the contrary, aren't. Take for example, flying deities: in Western mythology these creatures must be endowed with a pair of wings in order to fly, while in Chinese mythology, they don't need any equipment: they just need to give a flick of their sleeves to fly to the sky. From this perspective we can grasp the different systems of thought of Western and Eastern tradition which are rooted in different contexts. Western logic and Chinese unrestrained thought, after confronting each other for more than a century, now as a consequence of the advance of globalization, are continuously colliding into each other, as if they are gradually extending their own tentacles blending into the other.Chinese style, characterized by stillness, has to face the attacks of the fierce logic of globalization, and it has bravely absorbed what globalization has brought. Despite this, many people have risen to say that this process of absorption has actually opened up new territories to deeper understanding of our cultural identity. Therefore, the concept of post colonialism has widened, blurring the differences between being and not being, and the contrast between East and West, is or will give birth to an intricate and complex mythology. Qiu Anxiong, after stepping into both Eastern and Western cultures, has carried on his own analysis of the two, especially of their two different systems of thought. This was aimed at using Western logic within a Chinese context and frame of thought, thus re-creating and refining Western logic itself. While reflecting the common societal problems, he used an approachable way to show Chinese values.

The New Classic of Mountains and Seas is Qiu Anxiong's 25- minute long ink and wash animation that took part in 2006 Shanghai Biennial. It is said that this work had the highest viewing rate at the show. The work raised the public's interest not just because of its poetic and exquisite images similar to classic Chinese landscape paintings, and also not only because of the peculiar medium employed by the artist, but due to those large and wide unusual tricks projected onto the screen. The new and the old are complementary. ?From a certain angle, the new is a kind of re-development, and at the same time, something is new is not just a simple question of fetchism (grasping at or learning from as many past lessons as possible), being new implies a process of re-creation. Those who have read The Classic of Mountains and Seas know that although there are the absurd and uncommon within its stories, this book is not just a mythological tale. ?Through its all-encompassing content and diverse records, people can understand the level of development of society as well as the state of science and technology of that time.Therefore The Classic of Mountains and Seas on some level is a book which bears the weight of history; moreover it proves that since ancient times, mythology has often been regarded as a satirical but appeasing theme. From the point of view of the structure, Qiu Anxiong's The New Classic of Mountains and Seas has inherited the same method of recording of The Classic of Mountains and Seas by shifting ancient people's uncivilized eye towards reality in order to observe it. Like The Classic of Mountains and Seas, Qiu's The New Classic of Mountains and Seasdoesn't show any personal emotions, its records are non-judgemental. So from a certain perspective, we can affirm that the book faithfully records the history of that time. This method of observing through shifting the ancient peoples attention onto reality imbues the entire work with tones of mockery. In his work, the artist has created a kind of link: under the Western logic an Eastern illogic is combined with it, thus setting irrationality in the context of an uncivilized era and therefore creating an independent and separate system of observation.

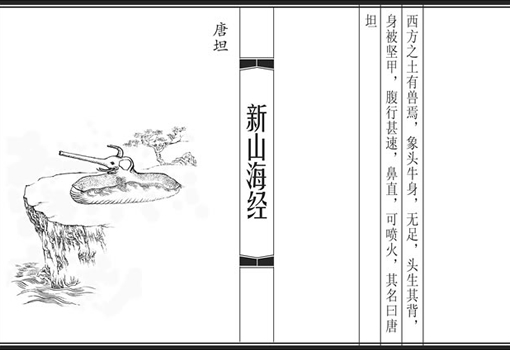

Starting from 2004 under the influence of this system of observation, Qiu Anxiong has drawn a series of modern monsters. He has placed annotations beside each, and finally ordered them in a catalogue.? Tanks, UFOs, autos, KFC restaurants are all modern things set before the eyes of ancient people which pervade the artist's The New Classic of Seas and Mountains. They are described as a metamorphosis of animals or as the combination of different objects of the everyday life. They are portrayed with neutral and objective strokes, devoid of any prejudice. Other records include what contemporary society has brought us: submarines, mad cow disease, the sheep clone Dolly, the appearance of abnormal five-legged frogs caused by the bombings of the US Southern Alliance using uranium-tipped ammunitions.These aspects have been added by the artist in his The New Classic of Mountains and Seas as phenomena unknown to the ancients. But, like the myths narrated in The Classic of Mountains and Seas, these recorded facts are also all satirical subject matter.? His animation works are born from his drawings of grotesque figures. This way, the artist shows his own theory of evolution of mythology. The New Classic of Mountains and Seas is the result of putting the birth of civilization, its development and its decline within an Eastern frame of thought in order to reflect on them. In the beginning water was created, then a crisscross of footpaths appeared, and from then on, civilization started its unstoppable path through the changes of dynasties and the course of time. Then the black bird was left behind, symbolizing the opening of the huge Pandora's Box of industrialization. Radical changes and all kinds of modern wild beasts all crawled out onto the scene. This explains the driving force and the scars of continuous evolution brought by the coexistence with postmodern civilization. In the end, what returns to the original state of peacefulness is peoples hearts. The combination of the ancient and the modern under the same time period and observing them from the same perspective, by putting everything into the whole picture using one another as a reference, it all results in a completely serene narration that can stimulate the viewer's reflection on contemporary civilization.This also proves that the value of art in this pretentious but trivial contemporary life perhaps lies in letting people return to the fullness of life. This ink and wash animation, which actually is not a true ink and wash, is the combination of about 5-6 thousand acrylic works on canvas by Qiu Anxiong. Without a doubt it marks a milestone in the artist's career.

?The last years spent abroad have stimulated Qiu Anxiong's reflection on his own cultural identity, thus spurring his desire for his native culture.? He thus started to study the work of Nan Huaijin and a series of Eastern classic writings.The deepness of Chinese culture and its meditative philosophical nature have stimulated the artists creative process and at the same time, let him understand how to use his Chinese culture to its best and create explosive new works. In 2004 after returning back to China, the artist started teaching at Shanghai China Eastern Normal University but continued to be moved by the same perseverant attitude towards art. His artistic language became more mature, and the initial perplexities, the up and down cycles the artist underwent at the beginning of his career, disappeared as can be seen from his works. Day by day the mood reflected by the dark tones of grey employed by the artist started to resemble more and more the stillness of heart of Chinese literati, standing aloof from worldly affairs.In 2005, the first solo exhibition of Qiu Anxiong Decoding time was organized by Shanghai based Biz-art center. The show featured mix media animations, photographs, installations etc., the artist employed to express the? relationship of men with nature, as well as to express the trivial, subtle, mutative, and sensitive nature of the fluctuations of the emotions of a persons inner world. In the air is an experiment with animation preceding The New Classic of Mountains and Seas that already fully embodies the artist's style. This work is filled with literati flavour but at the same time, revolves around the explication of that obscure deepness of meaning, which often characterizes contemporary art. But in this case it is explicated in an approachable way being completely devoid of any preoccupation of using a flamboyant language. Another work shown at the same time, Jiangnan Mistake is pervaded with ancient Chinese taste: the angle from which the images are shot, and a twelve minute- long motionless shot, make this work resemble a traditional Chinese painting. This work is filled with meditative tones, and at a certain extent it expresses the sentimental nature and the sense of detachment of Chinese literati. Airtight cabin,on the contrary, is a very romantic piece, expressing the train of thoughts taking place in a precise moment of time. The succession of the images, and the mood which encompasses the whole film make it resemble a stream of consciousness novel. In addition, the agile calligraphy of Qiu Anxiong, makes easy for the public to find a spiritual resonance with the work. The sculptures, installations, and photographs realized by the artist during this period, are even more direct since they acutely focus on urban development and on the various problems brought by the process of transformation undergone by the countryside. The themes touched by the works are deeply related to the artist's personal expression of his humanistic concern.

But, it is the artist's recent ink and wash animation that particularly interests me. This work is a continuation of Qiu's style animations, but at the same time adds new elements to the artist's artistic vocabulary. The feeling of resonance created by the images, allows the viewer to travel all over China during Republican times, from major cities to the countryside. The social scenery of the Republican epoch is vividly shown, and the use of background music and superimposed images, contribute to create a vivid portrait of the social life of the time characterized by the interlacing of hesitations, weak hopes and ideals hidden in peoples hearts, resulting in a feeling of common helplessness and vulnerability. The reason why Qiu Anxiong chooses this topic lies in the fact that it marks a breakthrough in defining what the audience is quite accustomed to see: in this work, Chinese modern history is compressed into different periods spanning from China's being a humiliated nation deprived of its independence, to its being a country resisting foreign aggression, from the period following the revolution, till the birth of new China. Here the artist blurs the boundaries between new and old, and once China is analyzed under the overall perspective of history, the Republican period results to be just one phase of the history of Chinas development. Moreover in our minds this period has already become blurred. The peculiar ideology of our times, and the huge changes occurred in the course of ten years, have contributed to shift the interest of many foreigners towards China. Despite this, foreigners seem to be particularly interested just in the period of the Cultural Revolution and in the years following it characterized by Chinas development and the birth of new social trends. This predilection has touched upon also art, since peoples incredible right to express their own taste is influencing at an increasing extent the production of contemporary Chinese art. Even if our epoch has already taken the distances from the trend of scar literature, it seems that we hadn't had enough of it. Perhaps it is because too much discontent and too many scars have been accumulated so far. Or perhaps the art market has some troubles. We do not know. Qiu's work seems to have escaped this confusion, since his self-contained stories are highly personal, and narrate just what the artist wants to express, avoiding to carry on any investigation of his art language. This genuine approach is very moving. In the large installation shown in U Space entitled Train spotting the images projected on the train's windows, are devoid of their historical sense, since they are just a new combination of memories, devoid of any common sense and cause-effect logic. Once history is cleared up what remains are just memories which are going to disappear.

The artist's exhibitions succeeding one after the other have made Qiu Anxiong become a workaholic. In a past interview he affirmed: The Classic of Mountains and Seas comprises different sections, the Southern Mountains, the Western Mountains, and the Northern Mountains, thus being a compilation of 320 records about history, geography and religion. I am thinking of adding new contents to The New Classic of Mountains and Seas, and after a long process of collecting records, each section will comprise from 30 to 40 objects. As he promised, he is actually carrying on this massive plan. His more recent The Classic of Mountains and Seas- part two is going to be ready soon, and compared to the first part this second one has a more compact rhythm, and its images are even more bizarre. Even if it resembles the previous part for its being a kind of chronicle of what happens in reality narrated with an ancient style, the narration of The New Classic of Mountains and Seas-part two is more vivid and amusing than that of the first part. The artist has given a personal interpretation of civilization. According to him, civilization means going beyond the triviality of reality, means carrying on a process of harmonization. Most of all, civilization is the universal principle that allows humankind to become what it is. Civilization means also alerting people who are lost in their daily confusion.

A pure heart can sometimes reveal the true meaning of life. Qiu Anxiong's theory of evolution of mythology can do the same, as long as we are able to face this work with an open mind.